'A Bearkat With Zebra Stripes' Is Super Bowl-Bound

Jan. 28, 2011

By: Frank Krystyniak, former director for SHSU's Communications Office

Note: Walter “Buddy” Anderson was featured in the "Alumni Look" section of the SHSU Heritage Magazine's February 2007 edition. In honor of his being named the head referee at Super Bowl XLV, held on Feb. 6 at Cowboy Stadium in Arlington, the Office of University Communications has decided to republish the original article in its entirety. The game will be broadcast at 5:30 p.m. CST on Fox.

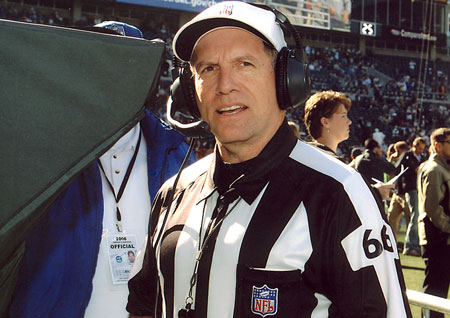

“Zebras” are what sports fans sometimes call the game officials because of their traditional striped-shirt outfits. Walt Anderson is a Bearkat who became a zebra—a four-year letterman as a kicker in football at Sam Houston State University from 1970–73—and is now at the top of the world of football officiating.

“Zebras” are what sports fans sometimes call the game officials because of their traditional striped-shirt outfits. Walt Anderson is a Bearkat who became a zebra—a four-year letterman as a kicker in football at Sam Houston State University from 1970–73—and is now at the top of the world of football officiating.

If you watch National Football League games you’ve probably seen Walt. As the head of his officiating crew—the “referee”—he gets to go on live TV and explain rulings on the field. He grew up in Texas and played high school football in Channelview, but he plays no favorites with either the Texans or the Cowboys.

“People are always asking me ‘who’s your favorite team in the NFL,’ Walt says. “I tell them ‘my favorite team is the officials.’

“You just don’t care who wins. We enjoy the game. We love the game but our role is to make sure it’s settled on the field, according to the rules.”

Most Cowboy fans remember the (January 2007) Wild Card playoff game when Tony Romo botched the hold on a Martin Gramatica 19-yard field goal. Most don’t remember that the official who had to make two key decisions in that game was Walt Anderson.

Both calls came late in the game. On the first a Dallas receiver fumbled the ball into his own end zone, and it appeared to have been recovered by Seattle for a touchdown. The Cowboys got the break on that one when Walt ruled that the Seattle player who recovered the ball had his foot out of bounds. It was a two-point safety instead of a touchdown.

Minutes later Dallas was driving toward the Seattle goal. On third down the receiver came up a half yard short, even though Walt’s crew ruled initially that he had made a first down. On this one Walt’s replay decision was not in the Cowboys’ favor.

The review showed that it was not a first down. The Cowboys tried a field goal that would have given them a late-game 23–21 lead, but quarterback/holder Romo mysteriously mishandled the placement and Dallas lost by a point.

“This is one of the hardest calls Walt Anderson will ever have to make,” announcer Al Michaels was saying in the broadcast booth as Anderson reviewed the play under the replay hood. After the game there was little criticism of the officiating.

When he was a Bearkat, Walt had no idea he would become a sports celebrity of sorts. He was all-conference in 1972 and academic all-America in 1972 and ‘73. After he graduated in 1974, he began study toward a dental degree.

He soon realized that football had been too much a part of his life—especially with his father, Mac Anderson, coaching in Florida and Texas—to step away from it completely. It was his father who encouraged him to look into officiating as a way to stay connected to the game he loved, and Walt started out doing little league and junior high and then high school games 33 years ago.

He moved into the college conferences—Southwest, Southland and Lone Star. While he chooses not to work Houston Texan games, because several of the coaches and players have been his neighbors, he has done a number of Bearkat games.

During his 11 years in the NFL he has worked four Wild Card games, three divisional championships, three league championships, and Super Bowl XXXV (New York Giants vs. Baltimore in 2001). That was the first Super Bowl in which instant replay was used. He was the line judge, made the first call challenged on instant replay, and was upheld.

Then last season he was selected to be coordinator of football officials for the Big 12 Conference. As if he needed something to do in his spare time.

He practiced dentistry in Sugar Land for 20 years and owned one of the largest group dental practices in the Houston area, with 13 doctors and 45 employees. Five years ago he sold his practice to devote full time to his officiating.

“Full-time” may not adequately describe the number of hours he puts in.

Many of those hours are spent in what he calls his “junior command center.” This is a media viewing and production room upstairs in his Sugar Land home, containing much of the same equipment as larger rooms in NFL headquarters in New York and Big 12 headquarters in Dallas.

His typical work week starts minutes after the last one ends.

By the time he has filled out his game report he is given a videotape that he reviews on the plane on his way to Dallas. Monday, Tuesday and part of Wednesday he’s in the Big 12 office. On Tuesday he gets another tape of his previous NFL game.

Early in the week he does a conference call with his crew. The NFL spends Tuesday and Wednesday grading each crew, and the crew chiefs get that report on Wednesday night—what Walt calls “the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

In the Big 12 he’s responsible for all aspects of the officiating—selecting new officials, assigning crews to games, reviewing and critiquing, and training.

He flies home to Houston Wednesday night and has another e-mail or conference call with his crew on Thursday, reacting to the NFL report. He spends Thursday and Friday in the junior command center, reviewing tapes of Big 12 games, of his crew’s last game if he feels it is necessary, and of the week’s upcoming game.

If they’re working an Indianapolis Colts game, for instance, they want to be sharp on no-huddle offense implications. They also pay particular attention to a team’s receiver patterns, because each potential receiver is watched by an official on each play. Often teams set out three receivers together, who then criss-cross in various patterns to confuse the defense.

“You don’t want to end up with two officials watching one guy and nobody watching the other one,” Walt says.

During the season on a typical day he gets up at 5:30 or 6 a.m. and gets to bed about 2 a.m. That makes for 19 – 20 hour days, seven days a week. His one luxury, when he travels to a game site, is to get to bed earlier so he’ll be more rested and less likely to make a bad call.

Over the years Walt says he has learned a lot from legendary NFL officials Jerry Markbriet and Red Cashion, as well as George Foshee, who he started with in high school.

Walt is not ashamed of how hard he works and why.

“I excel at preparation,” he says. “I don’t have the muscles of (Ed) Hoculi, or the height of (Terry) McCaulay. I put in as much or more time than any of them. That’s my strength—preparation.”

While he tries to maintain his neutrality when it comes to teams and players, over the years he has had some interesting interchanges, not all of which can be repeated in a family publication.

He recalls Bill Cowher, late in a game that the Steelers were leading comfortably, asking him “should we kick the field goal or run out the clock.”

“That’s not my job to make that decision,” Walt told him. But Cowher persisted. “I’d just run out the clock,” Walt finally offered. “You may see this team again in the playoffs.” Cowher took his advice.

He remembers that in the Cowboys playoff game in Seattle Bill Parcells was upset when he thought he was going to have to use a timeout. The play clock had not been started correctly, and Walt was in the process of fixing that.

While Walt was watching the replay, television viewers were watching Parcells give the line judge holy hell. What TV viewers did not see after Walt’s announcement that cleared up the problem was Parcells putting his arm around the line judge and apologizing for his impatience.

“That’s the kind of classy guy he is,” Walt says of Parcells. “He rarely questioned calls, but usually had a good reason. The Big Tuna needed more than a good reputation among NFL officials, however, “retiring” for the fourth time in January.

For the most part, coaches give him less grief than fans might imagine from some of their televised outbursts.

“They have so much pressure to win,” Walt says. “They snap sometimes but they don’t have too much time to get upset with officials. They have to get back to coaching.”

When he decides to hang up his striped shirt and cleats, he’ll have a lot of stories to tell about players as well. Like one exchange he had with one quarterback. As the “referee,” Walt’s job is to keep an eye on the quarterback, especially for late hits.

He recalls the quarterback complaining, “Walt, they’re holding.”

“I can either look downfield and not protect you,” Walt told him, “or do what I’m doing.”

“‘You just keep doing what you’re doing,’” he was told.

While Walt’s work is open to national scrutiny on every game he does, because of millions of critical eyes, an NFL official’s character must be unquestioned and his financial privacy is non-existent as far as the league is concerned.

“My finances are an open book to them,” he says. “They keep track of that.”

Unlike baseball umpires, most NFL officials have or have had other jobs. Members of Walt’s crew come from various backgrounds and live in scattered locations including Chattanooga and Knoxville, Tenn., Atlanta, and Findlay, Ohio.

The NFL officials pay scale is based on experience, from $2,500 per game to $10,000. Playoff assignments earn them additional money. Walt estimates that the average for an NFL official is about $80,000 a year, with the range being $45,000 to $160,000.

While NFL games are big business, deadly serious and highly competitive, they are also fun, Walt says. He wouldn’t put in such long hours and ask his family to sacrifice so much if they were not.

One of his most amusing moments, and one that shows his unbiased approach to his job, happened during a game in Miami. He was reviewing a ruling on the field that the Dolphins had scored a touchdown. While he was looking at replays he thought about his mother, who is a big Dolphin fan.

“My mother is watching this game,” he told the replay official in the booth, “and boy is she going to be mad when I reverse this call.”

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Director: Bruce Erickson

Assistant Director: Julia May

Writer: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail