Rune Work Uncovers 19th-Century Love Story

Aug. 1, 2012

SHSU Media Contact: Jennifer Gauntt

Story by: Kelly Garrison

|

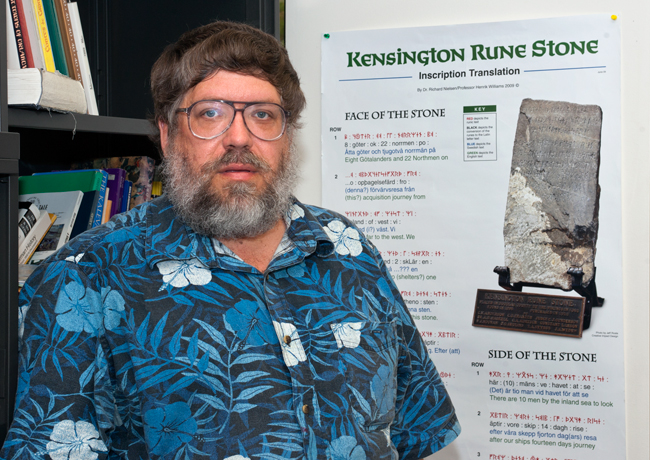

| In addition to teaching German in SHSU's foreign languages department, James Frankki devotes his time to studying runes, symbols used in early Germanic, Scandinavian and English writings that are now often found carved into stones. One of his recent projects included deciphering a stone found in Missouri that had never been completely translated. —Photo by Brian Blalock |

A mysterious set of stone carvings may have resulted in the gathering of some interesting historical information and confirmed a translation of ancient symbols for the first time in the U.S., but the investigation still leaves some questions unanswered.

Examined by James Frankki, assistant professor of German at Sam Houston State University, the stone, located on private property in Kansas City, Mo., had been studied before, perhaps as far back as 1922. But it seemed that no one could completely decipher the letters, until now.

Frankki explained that there are different definitions for “runes,” but they are commonly understood to be symbols used in early writing by Germanic, Scandinavian and English peoples.

Each one could have stood for just a letter, a number, an entire word, or a concept. They were often rich with symbolism, and interpretation of each symbol usually depends on some of the symbols around it, he said.

“On the Kansas City rune stone, one particular rune stands by itself. It looks like an ‘M’ and stands for ‘Man,’” he said. “How I interpreted it is based on the others. A ‘C’ stands for ‘Cwen,’ a woman or wife. Each letter stood for a certain concept. ‘Y’ meant ‘yew,’ the type of wood used to make bows. Or runes can stand for certain numbers, like the ‘C’ rune was ‘third,’ so it could mean ‘3.’”

In order expand his expertise in runes, Frankki has had to become familiar with ancient Germanic dialects, Anglo-Saxon, Old English, and Old Norse. He has spent a lot of time with medieval literature and studied other runes and sites where stones were carved.

He said that runes in the U.S. are surrounded by a complex controversy: who carved them and why, when, and whether they are “authentic,” the definition of which, itself, is rife with controversy.

“Most scholars have, until now, been using the term ‘authentic’ to refer to rune stones, which would have been carved during the period in which those particular runes were in current use,” Frankki said. “By this definition, we would say that the Kansas City rune stone is not authentic.”

Frankki said he would like to see that definition expanded to include, for example, a set of carvings that are used more or less correctly.

|

| (Above) Frankki studies the Kansas City rune. The pointing out of the straight line and three sets of double diamonds (just over his left shoulder) led to the ultimate discovery that the carvings were put in place to commemorate an 1888 marriage. (Below) The rune stone was discovered in a remote area on private property in Kansas City, Mo. —Submitted photographs |

|

“This (the Kansas City rune) would be the first North American rune stone to be considered ‘authentic’ by this definition. This is also the first one which has been dated, with confirmation by independent historical records, to a high degree of certainty. All others are either still disputed regarding provenance, authorship, and the dates when they were carved,” Frankki explained.

These particular carvings, and all of the questions surrounding them, reached Frankki by Internet.

“About January of 2011 there was a student at University of Missouri—Kansas City that posted a picture of this rune stone he had found on private property, which a colleague looked at and then sent on to me,” Frankki said. “We contacted him, and an archaeologist emeritus at Columbia helped set up this study. In 1965 he had gone and seen the rune stone himself, and he and a Danish scholar couldn’t figure it out.”

Frankki and a team of colleagues went to Kansas City to investigate, and when he looked at the runes, one symbol truly didn’t seem to belong. It was a straight up-and-down line, followed by three sets of double diamonds, which were stacked on top of each other.

When it was suggested that the first symbol was a numeric “1” and the rest could be “8s,” Frankki’s team decided to take a shot in the dark—could that be a year? And could these other symbols, referring to a man and woman, translated as “Cyrus Arthur Slater” and “Hannah Y,” be confirmed using census records or other city records?

Within hours, they had a confirmation by Internet, on Ancestry.com, that a wedding had taken place in 1888 between Cyrus Arthur Slater and Hannah Yearsley.

The team additionally confirmed the unknown lady’s name through a Kansas City Times newspaper obituary dated Oct. 1, 1954, for Hannah Yearsley.

Though these aren’t the only runes to be found in North America, this is the first time that a North American set of runes has been translated with dates and records to back it up.

“Most of the time it’s guesswork,” Frankki said.

Other carvings include a controversial set of runes in Minnesota, which places Norsemen there in 1362, a 130 years before Columbus. It is, however, a very long set of carvings and contains some errors outside of what is considered “correct” usage of runes.

“English immigrants knew the runes,” Frankki said. “The Ruthwell Cross in England is very famous; it has runes and Latin letters. This matches the Missouri stone.”

|

An up-close view of the carvings. |

Frankki hypothesized that Cyrus and Hannah knew the runes before they came to the U.S.; a book called Old Northern Runic Monuments of England and Scandinavia, by George Stephens, was available in the U.S. in 1866, when the couple was alive.

In the study of history, the facts might be confirmed, but questions about the people can still remain—who made the carvings and why? Why make the carvings on that spot? Are there more?

Frankki is fairly certain the carvings were done by Cyrus Slater himself.

“It’s a part of their heritage and culture,” he said. “Why not? It’s kind of a cool idea. What better way to memorialize your marriage?”

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail