History Prof's New Book Examines Elwha River History

Sept. 17, 2012

SHSU Media Contact: Meredith Mohr

|

Jeff Crane |

THE FIRST TIME HE STARTED THINKING actively about the Elwha River, a rushing body of water nestled in the mountains of western Washington, Jeff Crane was a college student hiking along its banks looking for trout, deep in the solitude of its environment.

It would be a few years before he would start writing about the river, but it was this environment that sparked an idea.

“I was above the two dams, deep in the mountains and there’s this beautiful little body of water, Lillian Creek, a tributary that feeds into the Elwha,” Crane said. “I stopped and I thought, what would this river be like with salmon in it? That was my active imagination, and I started wondering what had happened there and what had changed.”

Crane, associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University, has spent the past decade thinking about the Elwha River and its connection to environmental history.

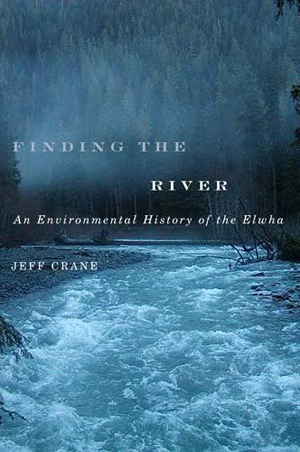

His recently published a book Finding the River, which was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award, focuses on what happened to the river and what the recent demolition of its dams has done for the ecological landscape of the area. There is also a documentary in the works by cinematographer John Gussman.

For many years, the Elwha was a vibrant, fluid ecosystem 41 miles long, chock full of 400,000-500,000 king salmon and steelhead. These salmon were formidable creatures that could jump up to 10 feet, and some grew to be six feet in length and over 100 pounds. It was also home to the four other species of Pacific salmon and the lower Elwha Klallam Indian tribe, a Native America tribe who have lived in the area for a couple of thousand years and depend on the salmon culturally and economically.

But in 1913 and 1926 two dams were built that decimated the run. Prior to the dam’s construction, each year the salmon would return to spawn in more than 70 miles of natural river habitat. But after the dams were built, only 4,000 salmon returned to habitats that were only 4.9 miles long.

In September 2011, the dams were removed, in what was the largest dam removal project in the history of the United States. The area of the Elwha is important because the watershed of the river is almost pristine, most of it being contained in Olympic National Park, according to Crane.

“This means that with the removal of the dams, there is a high likelihood of the salmon reestablishing themselves successfully,” he said. “The return of the salmon also benefits the watershed ecosystem by contributing nutrients from rotting salmon carcasses into the riverine and soil environment and providing food for species like black bear, coyote, raven, bald eagle, martens, and many others.”

Crane, who has been long captured by the beauty of the river as a native of Washington, said his book was “a project out of a passion of my own.”

“I wrote a lot of letters about the dam restoration in college,” Crane said. “I wanted to understand how you could go from it being 1913 and having a push to build the dam to build the industry and the river towns, with the lights and the opera houses, to less than 100 years later wanting to tear it down again. I wondered what ideas and values had changed, what had become scarce—like salmon. In the book, I wanted to get at the fundamental question—what changed?”

The Photographic History of Two Dams |

Through writing a book about the Elwha River, Crane researched answers to those very questions. His conclusions brought him to ideas about how society and the environment work together.

“I think we have, as a society, reached a point where we seek a balance between economic development and environmental health,” Crane said. “Hundreds of dams, most of them small, have been torn out across the country to restore river ecosystems. Flowing water creates greater aeration-this means more mayflies, stoneflies and more fish. There are multiple ecosystem benefits, which also create value for people.

“Environmental restoration is one of the key strategies of the environmental movement,” he said. “Dam removal, stream bank engineering, replanting and reintroducing of native species are all ways that environmentalists seek to correct some of the excesses that occurred with economic growth and development. The Elwha restoration is the largest restoration project so far.”

Crane said that the field of environmental history is a relatively new subfield, but one that has vital connections in history timelines.

“Environmental history involves looking at the geography of a place, like the Elwha River, and then looking at how the Indians used it historically, and then how the settlers used it,” Crane said. “It has different meanings for different groups. You never truly find the river.”

He is currently working on a book about American Environmental History for Routledge Press and also researching and writing a history of land use and conflict in the Powder River and Tongue River region of Wyoming and Montana. He also is doing readings and signings of his book in Washington and Oregon.

Crane explained that for each of the groups invested in the river, “Finding the River” has unique meanings for each.

“There is no static Elwha in terms of human relations with the river,” Crane said.

“For Indians it was a source of sacred power, a place they gathered the most important food in their culture and conducted important religious ceremonies, and also where they lived. For Thomas Aldwell and other businessmen and community leaders, the meaning of the Elwha was found in its ability to provide hydroelectricity to provide jobs, prosperity and build a thriving city,” he said. “For Elwha Klallam Indians and restoration advocates, the restored Elwha is a river that is significant for the return of the salmon but also as a recreational site, a symbol of improving environmental values, and as a monument to the successes of the environmental movement in accomplishing something that has never been done before-the removal of the two high-head dams to restore fisheries.

“The meaning of the river and its importance is shifting yet again as global warming has increasingly severe impacts on Pacific Northwest salmon,” he continued. “The Elwha River will be one of several ‘ark’ or refuge rivers where the ecosystems are healthy enough to protect native wild salmon over the next century or so. So, Finding the River also means finding the meaning of the river based on societal values.”

His strategy in constructing a book about the Elwha was to use a narrative, that would work in an academic setting and for people who live in the area and love the river.

His strategy in constructing a book about the Elwha was to use a narrative, that would work in an academic setting and for people who live in the area and love the river.

“It’s hard to bring those two audiences together sometimes,” Crane said. “I wanted it to pass muster in the academic world, but I also wanted people who were like me, wondering about the river as they hiked, to be able to read it. I meant for it to be accessible in prose, and so far I’ve gotten some good feedback, even from people who live in the area and picked it up out of curiosity.”

Crane spent a lot of time at the river and in Washington State reading archival material and researching during the writing process.

“I was at the dam a lot,” Crane said. “I wanted to see it and think about it and get the story right. Besides, it’s a river I love. I have hiked it multiple times, and there are elk, bear and a stunning landscape.”

For Crane, the meaning of “Finding the River” has continued throughout the process of learning about the Elwha and finally publishing a book about it.

“The title is based on one of my favorite songs, ‘Find the River’ by REM. It’s a song that explores the journey into life and finding your life's meaning,” he said. “It is applicable because those who used the river, dammed the river and restored the river, to some degree used the Elwha to find meaning in their lives, to try and accomplish great things. The Elwha had changed dramatically from before the dams were built and the idea is that once the dams are removed, the old river remerges, enters new channels, becomes the Elwha of old days as the salmon reenter it. In a sense, restoration advocates find that old river.”

Today, the dam is gone and salmon are already swimming upstream, Crane said. He hopes that others will read his book and think about the ideas of how environments and ecology change over time, and what we pull out of that to understand about America, how we use and value nature.

After that, Crane says another trip to the Elwha is in order, but not for research.

“I’m going to try to get back,” Crane said. “I’m going to see if I can spot a couple of spring Chinooks. And I’m going fishing.”

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail