Prof Revisits History To Examine Motivations, Redefine Native Experience

March 5, 2012

SHSU Media Contact: Jennifer Gauntt

|

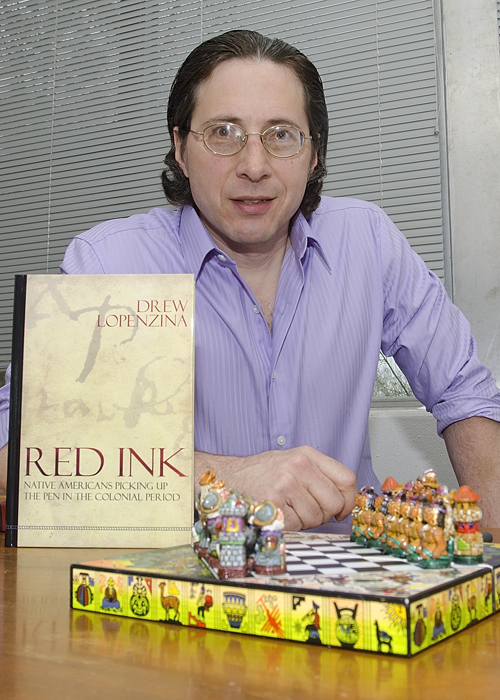

| A replica of the statue of Hannah Dustan sits on Lopenzina's desk. The original, on the island of Boscawen, N.H., is the first statue erected of a female in the United States. It heroicizes Dustan after she scalped and killed 10 Native Americans following an attack on her town and family by a different group of Indians. Not only were those she murdered from a different tribe, but they were Christian (or "Praying Indians"). Lopenzina teaches her story in his classes to show students the way that language was used in the colonial period to justify violence and "make it more palatable to an audience that may actually find it troubling." —Photos by Brian Blalock |

Native American lore tends to spring to mind a certain mythology for most Americans. Thinking about the earliest North American inhabitants may elicit images of the first Thanksgiving, the Disney version of Pocahontas, or perhaps the Mohicans of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales series.

“Whether consciously or not, I think that’s sort of the paradigm we all understand,” said Sam Houston State University assistant professor of English Drew Lopenzina, who specializes in both colonial American and Native American literature. “The dominant motif when we look at literature from the (early American) period—probably the classic Last of the Mohicans being the one that everybody knows—is that Native people are supposed to recognize their time on this part of the earth has come to an end; the white people are taking over now, and the Native people have to vanish, they have to leave the scene.

“It’s the trope of the ‘vanishing Native,’” he said. “We’re always looking at the last of the race, it’s always that last person who’s saying ‘it’s time for me to go; our time here is done.’ But Native people didn’t just vanish. They’re still here, although historically they have been forced from their lands and subjected to countless violent removals.”

The true Native experience is far from the romanticized version depicted in elementary classrooms or Hollywood movies. Though hidden behind colonial rhetoric, a distinct picture of the reality faced by Native Americans when British settlers colonized the United States can be unveiled even in the earliest writings.

In Lopenzina’s first book Red Ink: Native Americans Picking Up the Pen in the Colonial Period, he tackles one of the prevailing myths about the American Indian, that of literacy.

“We all have this idea that Native people didn’t write, that they were resistant to writing; really that Native people were somehow resistant to civilization itself,” he said. “This, in fact, is one of the reasons that white people thought it was OK to push them off their land.

“But it’s really quite different than that. Native people are engaging in literacy from the very first moments of colonization. They are trying to learn Western styles of literacy so they can engage in land transactions, sign diplomatic treaties, and even so they can read the Bible,” he said. “They had to engage with literacy because if they didn’t, they would continue to get cheated or ripped off or defeated in any number of ways.”

Native Americans also made significant contributions to some of America’s most vital early institutions, according to Lopenzina.

They were among the first graduates of Harvard University, which included a line in its charter about educating the “savages.” The first brick building at Harvard was erected to house those Native graduates who not only learned to read and write but took courses in mathematics, philosophy and could speak Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

Natives contributed to the first Bible printed in America, which was published in the Algonquian language in 1663, and “the first printing press in North America was maintained by a Native American named James Printer, who probably taught Samuel Green, our famous colonial printer, how to operate it,” Lopenzina said, adding that Samuel Green had no knowledge about printing before that time.

In both his book and in the classes he teaches on these subjects, Lopenzina said he hopes to not only dispel the myths that go along with the “romanticized” stereotyping of Native Americans but to show students the ways Native contributions were erased in the way that colonists recorded history.

“When I teach in the class, I’m trying to get my students to see those unintended consequences of the literature that we’re reading,” he said. “Colonists reflexively referred to Native peoples as ‘savages,’ ‘barbarians’ and ‘uncivilized.’ Natives were regarded as a people without any culture, art, law or religion of their own, and we tend to read these things and find this evidence pretty persuasive.

“When I teach in the class, I’m trying to get my students to see those unintended consequences of the literature that we’re reading,” he said. “Colonists reflexively referred to Native peoples as ‘savages,’ ‘barbarians’ and ‘uncivilized.’ Natives were regarded as a people without any culture, art, law or religion of their own, and we tend to read these things and find this evidence pretty persuasive.

“But Native peoples did have their own laws and customs—they were recorded in birchbark scrolls and wampum (shell beads used for commemorating historical events)—and it wasn’t uncommon for settlers who spent any time living with Natives to begin to recognize this culture as equal to that of Europeans.”

While considering this, Lopenzina is quick to point out that through his work he is not trying to paint Native Americans as victims but instead is showing how they adopted Western methods to form a quiet and constant resistance to what was going on around them.

“The trick is to understand that simply placing natives into the role of victimhood isn’t really doing anybody any favors,” Lopenzina said. “Resistance happens in a lot of different ways: it happens through non-compliance, it happens through open warfare or political actions or peaceful resistance, but it also happens through writing. Writing is a way that we resist the powers that be.”

Early native writers like Samsom Occom, William Apess, or Charles Eastman challenged the way the Puritan settlers viewed, or defined, them culturally. Through their works, they prove that they were aware of what the settlers thought of them and attempted to show those settlers that they weren’t what they were thought to be.

“In each of the narratives I am interested in, you see Native people trying to take matters into their own hands, trying to take charge of the discourse,” Lopenzina said. “Often the cards are stacked against them so you see the ways that they understand what forces they’re up against and how they’re trying to negotiate those powers, usually in pretty savvy ways.”

While Native American literature is considered an “emerging” field, Lopenzina said it is one that is growing quickly.

“Just like African Americans and women had to work their way into the university institution, it took a lot of time for Native people to get there as well, and that’s for economic, social and historical reasons,” he said. “But they have gotten here, and now that they’re here there’s been a real sense of rethinking how this story has been told, revisiting our past and recognizing some of the misconceptions that have been perpetuated.”

Most scholars, he said, do not look at the native experience in colonial literature but instead focus on the literature of the 19th and 20th centuries, “where everybody assumed most of the action was” because of authors such as Cooper.

“For me, what makes this an interesting project is it’s reaching a little bit further back and realizing that there are Native literary traditions that extend all the way to colonial times, and, in fact, even prior to colonial contact where Natives have their own forms of literacy that they’re using in wampum and winter counts (symbols used by plains Indians, like the Sioux, that were painted on their teepees as calendars that recorded time by marking the most significant event of each year) and awikhigans (marks left on trees and rocks that recount the details of a hunt or a war party) and things like that.”

A native of Massachusetts who grew up surrounded by the Plymouth lore, Lopenzina said his interest in native literature stemmed from “the kind of well-intentioned romantic ideas that most people have.” In graduate school, while studying American colonial literature, his two interests began to collide.

While he says he hopes his work helps change the way people think about the colonial period and native involvement in that period, Lopenzina acknowledges that his work hasn’t come without some resistance of its own, both in the classroom and amongst other professors.

“The fact is it’s always a slow process,” he said. “You have to treat other people’s ideas with respect, but you have to keep pushing and keep educating and you hope ultimately you turn them around.”

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail