English Prof Gets 'Graphic' In First Book Publication

Nov. 15, 2013

SHSU Media Contact: Jennifer Gauntt

|

| Michael Demson, whose areas of expertise include transatlantic and European romanticism, found a random reference to Percy Shelley connected to the American labor union movement. As he began exploring the connection, he decided to turn his work into a graphic novel and started teaching a course on graphic novels in SHSU's English department in prepration. He also teaches classes on world and ancient literature. —Photo by Brian Blalock |

At first glance, they appear to have nothing in common.

He was a famous Romantic poet, an atheist born of privilege in 18th-century England; she was a factory worker-turned-labor union reformer, a Lithuanian-born Jewish immigrant whose rabbi father had been dragged into the streets and beaten to death because of his faith, leaving their family with nothing as they relocated to New York at the turn of the 20th century.

But during Pauline Newman’s early life on the lower east side of Manhattan, their paths crossed. As she sought out literature to learn the English language, Newman encountered the works of Percy Shelley, and there, they found common ground.

Shelley, a hotheaded, politically-charged radical—who was kicked out of Oxford for writing a pamphlet that demanded his professors prove the existence of God or stop talking about him altogether—became a source of inspiration for Newman and a movement she would lead during a critical time in her life, a time that would label her, too, a radical.

Their story became a source of inspiration for Sam Houston State University assistant professor of English Michael Demson, and he shares it in his first book.

Masks of Anarchy: The History of a Radical Poem, from Percy Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire is not what one might consider a typical research endeavor; its form may even lend itself the distinction of being “radical” by scholarly standards.

"Masking" History |

|

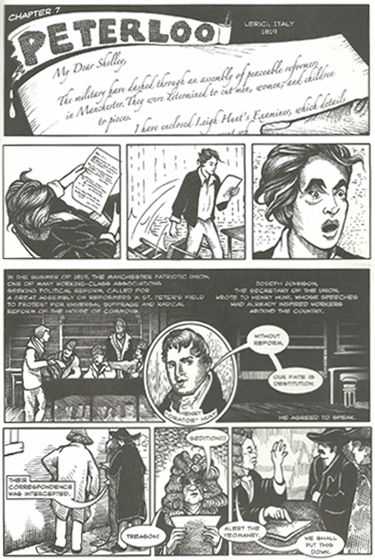

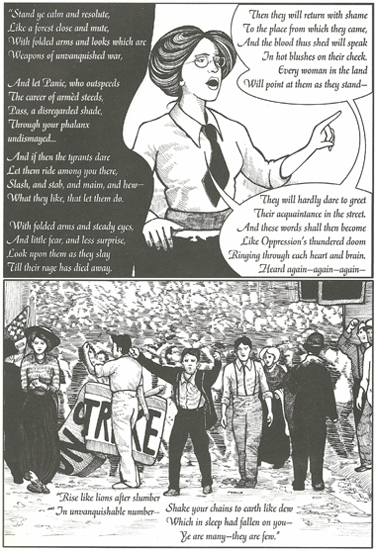

| Demson wanted to make the stories of Percy Shelley's "The Masque of Anarchy" and Pauline Newman's career as union reformer more accessible, so he translated British and American history into a graphic novel. These pages depict Shelley being "inspired" to write his famous political poem (above) and Newman "inspiring" the masses by quoting it (below). —From Masks of Anarchy, Illustrations by Summer McClinton |

|

“It is a graphic novel in the sense that it is an extended comic book, but it deals with adult themes,” Demson said. “It is non-fiction in the sense that it’s a history of both the inspiration for Shelley’s poem ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ and its second life when it became very popular in New York City at the turn of the 20th century, where the poem was picked up by labor organizations and used to organize union workers.”

The project began when Demson, who had just completed his dissertation on Shelley and French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau at The City University of New York, found a “curious” reference to Shelley in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

“I thought this was bizarre because I had always heard that Shelley had a popular working-class readership in the decades after he died, in the 1830s and 1840s, but then it’s widely thought that that readership petered out. It was startling to me to read a Jewish immigrant quoting Shelley in Manhattan a hundred years later,” Demson said.

He began to examine Newman’s use of Shelley’s poem in her work as the first female organizer of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union for an academic article, which was published in a “fairly prestigious academic journal.”

But, as he worked, he became so excited about the project that he wanted to make it more accessible to a broader audience than the specialists who would pick up the European Romantic Review.

When he learned that during that same period a “very vibrant circle of artists in New York,” the Ashcan group, also were developing the multi-paneled comic strip, the idea to turn his research into a graphic novel began taking shape.

“I thought, ‘wow, this is really an interesting coincidence, that when Pauline Newman was working to build the unions through Shelley’s poetry, there were also cartoonists creating narratives about the life of the urban poor in New York at the same time,” Demson said. “I thought if I could find an artist who could take that style of the early American cartoons and use that to tell Pauline Newman’s story that there would be a nice synergy there.”

With the help of illustrator Summer McClinton, Demson put together the 128-page graphic novel, intertwining the stories of Shelley’s writing of the poem with Newman’s life, career and her use of the poem to inspire the masses.

The finished product incorporates two styles of illustrations that highlight the different time periods found in the graphic novel—for chapters on Newman, drawings are retro, representing the Ashcan group era, and for chapters on Shelley, the drawings follow in the romantic and satirical style of pamphlets from the 1820s.

“In thinking through the reader, I decided I didn’t want to tell the story and just have illustrations that go along with it; I really wanted the illustrations to tell the story as much as the text would,” he said. “When I think visually in terms of a comic book, I’m almost always thinking two dimensions, that the characters are always walking right to left or left to right, but Summer was able to say ‘we can have them walking in or out of the pictures.’ (In the finished product) oftentimes characters break frames, so it’s really bringing it much more to life.”

Demson, a Toronto native, said growing up he was only somewhat a fan of graphic novels, having read some of the more famous works, such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Fun Home by Bechdel.

“Once I started working on the project I realized I needed to spend more time understanding the form so I went out and bought a bunch and started going through the history of satirical imagery and caricatures,” he said. “Since I’ve been at Sam, I’ve taught a course on the history of the graphic novel (that is still offered on a cycle through the English department), which really allowed me to gel my thinking about all of this stuff.”

He particularly sought out books that meshed the politics he was examining, which is where the stories of Newman and Shelley converge, both in the climax of his graphic novel and in real life—with the tragedies that inspired their greatest works.

Ye are many — they are few

While Demson’s Masks of Anarchy connects the lives of Shelley and Newman through ideas of radicalism, it is what they were fighting against, and for, that is central to the graphic novel.

“The Masque of Anarchy” was written in 1819 as a response to the Peterloo Massacre, wherein 14 were killed and hundreds were injured while peacefully protesting in demand of government reform in Manchester.

|

| Demson's graphic novel was published in July by Verso. |

“When Shelley gets wind of the Peterloo Massacre, he is so outraged that in a sort of fit of fury he writes ‘The Masque of Anarchy,’ which has been called the greatest political poem in English,” Demson said. “It’s really his response, denouncing the government for this brutality against the people it’s supposed to protect.”

Likewise, Newman had just left her job at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory to become a union organizer when the infamous fire broke out that left 146 garment workers dead. Employees were locked in the building, and many attempted to save themselves by jumping from the eighth through 10th floor windows.

“She reads about it in the paper, rushes back to New York to find out which of her friends had died, and there’s this sort of mutinous sadness about what’s happened, and she immediately starts quoting ‘Masques of Anarchy’ to raise people’s awareness,” Demson said. “There’s one stanza that you see suddenly spreading across all the union papers, which is the final stanza of the poem, which is ‘Rise like lions after slumber…ye are many, they are few.’”

In researching Newman’s life to create Masks of Anarchy, Demson came to see that in using Shelley’s stanza as a rallying cry, Newman is taking the action that Shelley’s poem bids the people to take.

“(In Shelley’s allegorical poem) Hope becomes this figure that’s this sort of airy, light woman who rises up to stand opposed to the government, to call them out, expose them, as frauds, as thieves, as belligerent monsters, essentially,” Demson said.

“I like to say that Shelley inspires the poem, but Pauline Newman really embodies it,” he said. “She is that figure who stands up and calls out the tyranny of the laboring conditions in New York, who stands up and says, ‘we need to shed light on what’s actually going on in these factories, and we all need to rise because we are the many.’

“Hopefully, the end of the graphic novel really comes to show Pauline Newman as that Hope, as that embodiment of courage, in that fight for equality.”

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail