Forensic Scientist Works To Preserve DNA In Natural Disasters

Nov. 18, 2013

SHSU Media Contact: Beth Kuhles

|

| Sharee Hughes-Stamm is one of the newest faculty members in the College of Criminal Justice's forensic science department. She brings with her a host of experience in DNA analysis and her work has taken her all over the world, exploring ways to identify victims of natural or mass disasters. —Submitted photo |

For as long as she can remember, Sam Houston State University assistant professor of forensic science Sheree Hughes-Stamm has been fascinated with how the body works.

“When my dad would take my sister and me fishing as small children, I wasn’t interested in holding a fishing line, I just wanted to cut up the bait and dissect out the squid eyes,” she said.

This fascination with anatomy grew in high school where biology was her favorite subject because of her love of dissecting things.

“The first thing we dissected at school was a bull’s eye, and I was hooked,” Hughes-Stamm said. “After that, we dissected toads, rodents, chickens and sharks, and I knew I wanted to be an anatomist.”

This passion for anatomy was nurtured in her undergraduate studies majoring in human anatomy, when after her first forensic osteology class handling human skeletal material, her passion for forensic anthropology and processes of human identification was born.

At Bond University in Australia, Hughes-Stamm pursued her doctorate in forensic genetics and began linking her forensic anthropology knowledge of bones with DNA analysis to help identify highly degraded skeletal remains such as those that would be encountered after a natural or mass disaster.

|

| Hughes-Stamm examines bones found at a mass grave in Croatia. |

She said her interest in mass graves grew out a workshop she attended in Washington, D.C., just three months before the 9/11 terrorist attacks. After that tragedy, and the Bali bombings and the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami in Indonesia, she decided to explore degraded DNA samples for her doctoral dissertation.

She also worked on a National Institute of Justice grant to develop a panel of genetic markers that could predict various phenotypes based on a DNA sample, a tool that can be used to determine the ancestry, eye, skin and hair color of a missing person or an unknown perpetrator who had left biological evidence at a crime scene. In addition, She has explored on how water, heat, and surface or submerged burials affect the success of DNA typing in bone samples.

Her work took her to Croatia and Bosnia to observe the work of the International Commission for Missing Persons on mass graves from wars in those countries. When the tsunami hit Southeast Asia In 2004, resulting in thousands of fatalities, her friend and mentor—the director of the forensic DNA lab in Thailand—discussed the problems encountered when identifying so many victims in hot and remote conditions.

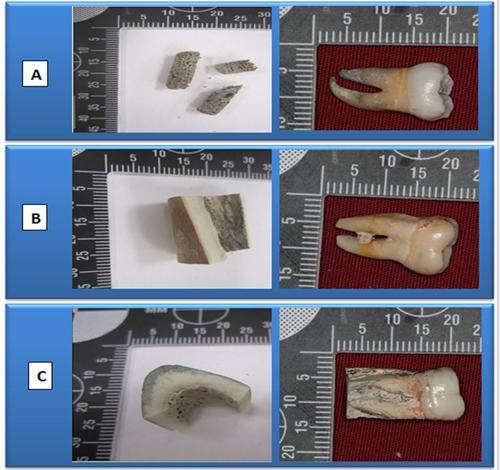

It also led her to conduct a trial on a new technique to extract DNA from teeth, one that preserves the integrity of its structure. To get to the core of the tooth, which contains the most intact DNA, many scientists were cutting across the crown or removing the entire root structure, destroying the ability to use the tooth to provide additional clues for identification.

The technique that Hughes-Stamm used was less invasive—she went in through the root, leaving the structure intact, which allowed her to get good, quality DNA samples from the teeth.

“Historically, we destroyed the teeth by drilling holes in them or cutting them in half,” said Hughes-Stamm, who presented her research to the Society of Forensic Science at Sam Houston State University earlier in the year. “But the architecture of teeth are important for study, and you can’t destroy ancient samples on loan from a museum.”

Her subjects for this project had been dead for more than 200 years—they were three victims of the 1791 shipwreck of the HMS Pandora, which was on a mission to retrieve mutineers from Capt. William Bligh’s HMS Bounty when it sank off the coast of Australia.

Hughes-Stamm analyzed teeth and small bone fragments using DNA-typing and discovered that a bone from one victim had been mislabeled in a museum display when it actually belonged to another.

She still has small samples from “Tom," "Dick" and "Harry,” the nicknames given to the first three victims retrieved from the shipwreck site. While only 20 percent of the site has been salvaged and more than 200 bones and bone fragments have been retrieved, even 200 years later, these bones may yield clues to the identity of the victims. A project is underway to use DNA markers on the Y-chromosome to trace male descendants of the victims.

|

| Bones fragments and the teeth of three victims aboard the HMS Bounty, whom Hughes-Stamm now refers to as Tom, Dick and Harry. A 24-gun frigate, HMS Pandora was sent by England to Tahiti to capture mutineers from the HMS Bounty, which had been sent to the West Indies to collect plants for crops. Fourteen were captured and were being shipped back aboard the HMS Pandora when it sank in the Great Barrier Reef. Thirty-one members of the crew and four prisoners perished. A collection of about 200 bones found on the HMS Pandora. |

All of her experiences have led to her latest study—to find new techniques to preserve tissue samples and speed up the DNA identification process in mass disasters, such as hurricanes, tsunamis, terrorist attacks, wars or acts of genocide. Her work is being funded through a grant from the National Institute of Justice.

“In these circumstances, forensic personnel may be faced with the task of identifying hundreds or even thousands of bodily remains in a very short period of time,” said Hughes-Stamm, who joined the College of Criminal Justice’s Department of Forensic Science in 2012. “Through improvement in the collection and processing of tissue samples for DNA analysis, we can identify more victims and help bring closure to those who would otherwise never know what happened to friends and family.”

During natural and manmade disasters, forensic teams often face adverse conditions, such as remote locations, intense heat, and the lack of electricity and resources.

As a result, bodies may be left to decompose rapidly in the heat, creating a health hazard and also making genotyping more difficult as the DNA in those remains is also degrading.

As part of her research, Hughes-Stamm will test several different solutions, both commercial preservatives and in-house mixes of readily available chemicals—such as various salts, solvents and alcohols—to provide a better way to collect, preserve and store tissue samples from the deceased. The study will focus on maximizing the quantity and quality of DNA leaching from the tissue into the surrounding solution so that this “free DNA” to help speed up the identification process.

The research will be conducted at SHSU’s Southeast Texas Applied Forensic Science Facility, a state-of-the-art willed-body donor facility dedicated to scientific research and training. It is only one of six facilities in the country to use human body donations for the purpose of forensic science research. Tissue samples for this research will be obtained from cadavers at STAFS at various stages of decomposition.

For Hughes-Stamm, the project is about helping to put a name and face to every treasured friend and loved one who may be lost in a natural or mass disaster, so their families can gain some closure.

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail