Historian’s New Book Examines ‘Value’ Of Democracy

Aug. 19, 2014

SHSU Media Contact: Jennifer Gauntt

|

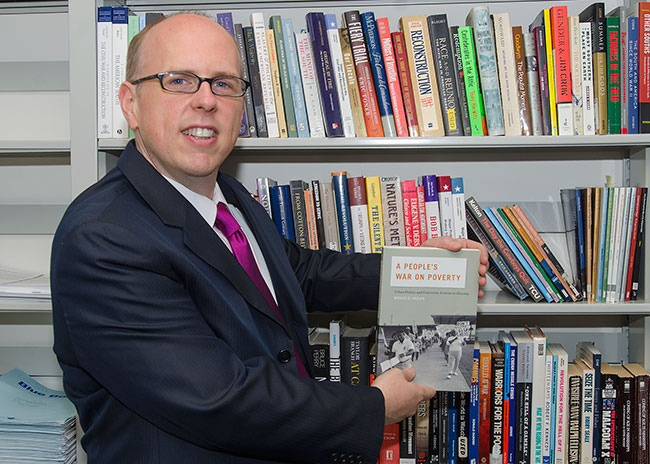

| In a time when the democratic process is being challenged on both the national and state levels by Supreme Court decisions and state legislatures, assistant professor of history Wesley Phelps takes a look back through his new book on Houston in the 1960s, when the poor there found empowerment through Lyndon B. Johnson's Economic Opportunity Act. —Photo by Brian Blalock |

When historians have written about Lyndon B. Johnson’s Economic Opportunity Act, they’ve largely considered it a failure, in that it didn’t actually wage a “war on poverty,” as Johnson had intended, according to Sam Houston State University assistant professor of history Wesley Phelps.

But in the 50 years since that legislation kicked off what became known as the “War on Poverty,” a new cohort of historians—those who are examining the effects of the legislation on local levels—are seeing something different.

While the “War on Poverty” may not have reduced the income inequality of the poor across the country, those in Johnson’s home state may have struck it rich in another key area, perhaps as an unintended consequence.

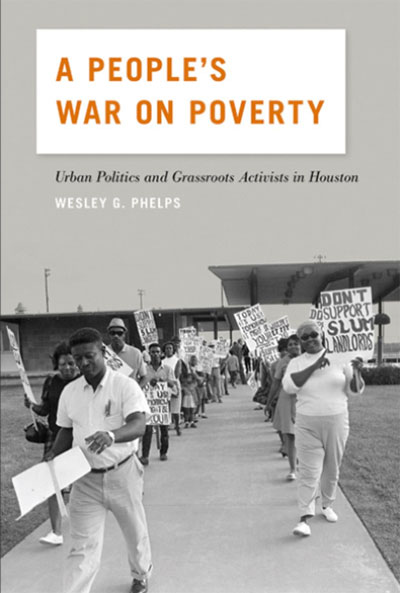

Phelp’s new book, “A People's War on Poverty: Urban Politics and Grassroots Activists in Houston,” details what Phelps calls an “important part of the story” of the EOA in the mid-1960s.

Through policies and agencies set up by the EOA, an intersection emerged where the Civil Rights Movement and the poor in Houston met—at the corner of politicization and empowerment.

“What I try to argue in the book is that the war on poverty opened up a space to challenge mainstream definitions of democracy,” Phelps said. “Allen Matusow (Phelps’s adviser and history professor at Rice) argued that the war on poverty could never redistribute income and, therefore, it never could really deal with poverty. What I’m arguing is that, actually, what the war on poverty did was attempt to redistribute power; there was this component of the war on poverty called the community action program and it did attempt to politicize and empower the poor.

“Movement activists who were on the ground, implementing the war on poverty, organizing poor people, launching protest marches, showing up to city council meetings—what these activists and the poor did in Houston was they offered a different vision of democracy that was much more participatory, in that everyone—no matter how rich or poor they were, no matter what the color of their skin was, no matter what gender they were—they would play a role in making the decisions that affected their lives,” he said. “That’s the vision of democracy they had.”

When a group of activists came together to protest the lack of public water services in a low-income, African-American neighborhood on the northeast side of Houston, for example, the group realized that putting democracy into action was effective; the city council immediately began constructing a city water system.

When a group of activists came together to protest the lack of public water services in a low-income, African-American neighborhood on the northeast side of Houston, for example, the group realized that putting democracy into action was effective; the city council immediately began constructing a city water system.

“That empowered these activists in a way,” Phelps said. “It didn’t bring them out of poverty, but it certainly gave them more political power.”

And perhaps it worked a little too well.

As groups began organizing to put more and more pressure on the power structure, a group of conservatives began pushing back by interfering with these movements in a series of moves that ultimately brought about an end to the “war on poverty” in Houston.

“The war on poverty was designed so that the money and the programs that were supposed to target the poor through these community action agencies, which were supposed to be independent of the mayor and local

power structure,” Phelps said. “Some cities, likes Chicago, had these machine political systems and the local government took control of it immediately, but in places like Houston, there was no mechanism for the mayor to do it.

power structure,” Phelps said. “Some cities, likes Chicago, had these machine political systems and the local government took control of it immediately, but in places like Houston, there was no mechanism for the mayor to do it.

“For a while, it was operating independently (in Houston), but, gradually, the mayor realized what’s happening and found a way to get control of it,” he said.

One of the ways they did this was by controlling the message when demonstrations went wrong and spreading fear by labeling the poverty program “haven for radical, dangerous people.”

An example of this is the 1967 Texas Southern University “riot,” wherein a couple of demonstrators threw some bricks at passing cars and police were called in.

“The next thing you know, the police are there in riot gear and they claim that there were shots being fired from the dormitories. So the cops shoot 2,000 rounds into the men’s dormitory; they succeed in killing one person, one of their own—a bullet ricocheted back and killed an officer,” Phelps said. “What the mayor, Louie Welch, was able to do was say that there were people who were working with the war on poverty who had been on campus stirring up this kind of trouble.”

Eventually, after various attacks led by the mayor, police chief and then-Congressman George H.W. Bush, the program became too much of a liability for Johnson and the Office of Economic Opportunity, and they stopped supporting the programs, according to Phelps.

But Phelps is also quick to point out that some of the blame also goes on the activists, because they just underestimated the power of their enemy.

“I don’t want to underestimate the opposition, because it was enormous: to have the mayor and a congressman and the police chief lined up against you, those are enormous odds,” he said. “But I do think to some extent, they never really considered those odds.”

Ultimately, Phelps concludes that the vision was defeated by a much more conservative vision of democracy that would actually limit the political participation of poor people in Houston.

“That’s the legacy we’re still living with today,” he said.

Studying Houston

“A People's War on Poverty,” published in March by the University of Georgia Press, was originally Phelps’s dissertation topic at Rice University.

He chose to examine the effects of the legislation in Houston because his academic interests tie into “pockets of civil rights history that we don’t really talk about.”

“If you look in the standard history of the Civil Rights Movement, and even if you look at some of the histories of the City of Houston, you might get the impression that there was no Civil Rights Movement in Houston, that what happened is that whites decided sometime in the late 1950s that the city should be desegregated, so they just did it; that it was peaceful and there weren’t any protests or sit-ins or marches,” Phelps said.

|

| A review: "Wesley Phelps reveals a largely unacknowledged Houston. He tells a story of poverty and power through a series of moments when a diverse group of local people told a generation how things had to be different. Battling over ideas from prophetic Christianity, the radical New Left, the emerging Sunbelt, the Old South, and the controversial War on Poverty, they launched a fierce argument about the kind of power that working Americans should have and the kind of Houston that would emerge from the end of Jim Crow.” —Kent B. Germany |

“This is a city that is neglected by historians, it’s neglected by urban historians, and, particularly, it’s neglected by Southern historians, many of whom don't even consider it to be a part of the South,” he said.

When he started on the project in 2007, the country was reaching the heights of modern income inequality, and he has found that subject is topical in ways that have become more relevant in today’s political climate, particularly in relation unions (he feels that reports that the poor in Europe are outpacing the poor in America are due to the European countries’ Labour Party working on behalf of the working class), income inequality and race (he believes the war on poverty was “absolutely a racial issue”).

Because his research focuses on how democracy works on the ground (upcoming projects include a feminist anti-nuclear organization and the AIDS crisis in the urban South), he’s especially concerned about the recent Supreme Court decisions that may remove “the democratic process from regular people more and more.”

“Over the last 10 years, what we've seen is a narrowing of the definition of democracy, and we can see this in a number of ways: redistricting plans that silence the voices of the poor and racial minorities; voter identification laws that disfranchise poor and minority voters; all the way to the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which uncapped political donation limits made by corporations," he said. " I think we could even look at the McCutcheon decision—the idea that rich people can give more money to political candidates.'"

“All of this suggests that over the last decade or so, there has been a narrowing of the definition of democracy. The vision of democracy that activists in Houston had was there for a brief moment and was defeated," he said.

So how do people stay optimistic about the democratic process, when all of these things seem to subvert it?

Phelps believes the answer is in the history books.

“I think we can see equally daunting odds in the past, and I think the 1960s are a good place to look,” he said. “The '60s showed us that individuals matter and can influence the course of history; it’s up to the activists to keep those fires going.”

He also believes that the answer ties in with his mission as a teacher at Sam Houston State University.

“As we’re becoming so divided, between the wealthy and everyone else, the gap is getting bigger—I think education is such an important part of that,” he said. “I really believe in educational democracy; I believe everyone deserves a good education.

"I taught at Rice University and the University of St. Thomas before coming to SHSU, and I teach exactly the same way here that I did in those places. I think every student here deserves the same quality of education that students at Rice or St. Thomas are getting. I really believe in the mission of this university."

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office

Associate Director: Julia May

Manager: Jennifer Gauntt

Located in the 115 Administration Building

Telephone: 936.294.1836; Fax: 936.294.1834

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

SamWeb

SamWeb My Sam

My Sam E-mail

E-mail