Return to 'Freedom Summer'

|

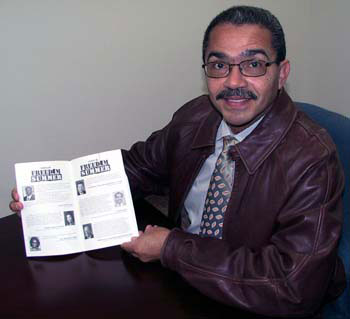

| Anthony Harris And Program From Drama

'Freedom Summer' |

Anthony Harris and the Civil Rights Movement grew up together.

Harris was just a baby 50 years ago, May 17, 1954, when the

U. S. Supreme Court ruled that separate but equal was not

an appropriate response to the race issues threatening to

rip apart the United States.

Ten years later as a pre-teen, about the time of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, he was participating in marches, demonstrations,

sit-ins, boycotts, and voter registration drives. That year

is now known for its Freedom Summer.

Despite these efforts, many in Harris's hometown of Hattiesburg,

Miss., were still not allowed to vote. Schools remained separate

and unequal.

On a cold and rainy January day in 1965, Harris and two of

his friends were arrested for picketing the Forrest County

Courthouse in Hattiesburg.

They were thrown into a police car. Officers threatened first

to feed them to their police dogs, then to beat them with

a blackjack club.

They were released when Harris's mother burst into the interrogation

room, defied the officers and demanded they free the boys.

In the fall of 1966 Harris was one of five teenagers who chose

to integrate Hattiesburg's W. I. Thames Junior High School.

This was four years after James Meredith had enrolled at the

University of Mississippi, setting off a riot that led to

the death of a French journalist.

Anthony Harris survived those times and maintained his interest

in education, earned his doctorate, and now teaches at Sam

Houston State University. On Tuesday he returns to Hattiesburg

High School to introduce a student play that includes the

incident of his arrest 39 years ago.

On Thursday night James Meredith will introduce that play--"Freedom

Summer."

"My own recollection of Freedom Summer contains memories

of being taught by folk singer Pete Seeger to play the guitar

at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church Freedom School," Harris

wrote in the play's program.

"Walking the dusty roads of black Hattiesburg in the

sweltering heat helping with voter registration drives, and

being mesmerized by the performance of Purlie Victorious and

In White America at St. Paul United Methodist Church by a

group of thespians known as, The Free Southern Theater, founded

by Gilbert Moses.

"My most enduring memory, however, is of my mother, who

modeled and instilled in her children the courage to stand

for what is right and to resist evil in all of its manifestations,

no matter where we find it."

Other memories include being spat upon, being repeatedly called

that most awful "N" word, and enduring biased teachers

who could not see beyond his color when it came time to assigning

him grades.

The worst may have been hearing his white classmates cheer

the death of the person who instilled in him his appreciation

of non-violence.

He remembers he had "never felt as tormented, as alone,

as friendless," as when classmates cheered and joked

about the April 5, 1968 shooting death of Martin Luther King.

"Regrettably," he says now, "I find it increasingly

difficult to persuade young people to accept the principle

of non-violence."

Then he quotes King.

"'If, as a nation, we continue to follow the retaliatory

notion of an eye for an eye; tooth for a tooth, we will end

up being a blind, toothless society.'"

Not only has Harris practiced non-violence, he has worked

within education to better society. He started a program for

at-risk black students called Project Keep Hope Alive in Commerce,

Texas, where he taught before coming to SHSU last year.

Also while in Commerce, he was active in public schools as

well. This might seem natural for a professor of education,

but he has gone beyond a casual interest, serving as a school

board member for 15 years, including six as a board chair.

"Through the altruistic efforts of transforming the lives

of many young African American boys through Project Keep Hope

Alive and the experience of being a young participant in the

civil rights movement decades earlier, my own life has been

unalterably transformed," said Harris.

"And in the process, I have become more deeply committed

to the notion of social justice, not as an abstract concept

but as a living, breathing attainable goal, to which all communities

and peoples are entitled."

- END -

SHSU Media Contact: Frank Krystyniak

February 2, 2004

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu

|