Biology Profs, Students Dig Into Africa

|

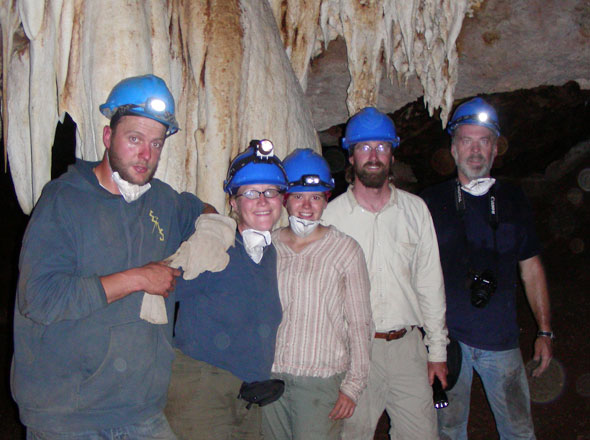

SHSU graduate student Tim Campbell,

Texas A&M graduate student Juliet Brophy, SHSU junior

Alicia Kennedy, assistant professor of biology Patrick

Lewis and biology professor Monte Thies (from left)

explore a cave in the Republic of Botswana that has

had very few westerners inside as part of an archaelogical

dig for fossils over the summer. —Submitted photo. |

The nearest water was more than five hours away; the nearest

doctor, as many as four days away.

They slept in tents, had no running water, subsisted mostly

on canned food, spent their days digging in the dirt and traveled

with a foreign military.

It may not sound like an ideal way to spend your summer, but

it was all in a day’s work for several members of SHSU’s

biological sciences department.

Assistant professor of biology Patrick Lewis, biology professor

Monte Theis, junior Alicia Kennedy and graduate student Timothy

Campbell were part of a team that spent six weeks this past

summer in South Africa’s Free State Province and the

Republic of Botswana, exploring cave sites and extracting

fossils dating from one to four million years old.

South Africa’s Free State Province

In the 1950s, the South African government was digging through

a hill to put in a railway, and while doing so, they exposed

buried sediments and fossils, including a 6-foot long mammoth

tusk.

Now known as the Meloding Railway Cut site, it has been dated

to be over four million years old, according to Lewis, who

has been working in South Africa since 2002 and is co-directing

the current project with Darryl de Ruiter from Texas A&M

University.

“This is a time period in southern Africa that there’s

virtually nothing known about, so it’s a real exploratory

spot,” he said.

The SHSU team spent about a month in the area, using a big

backhoe in a field next to the railway cut to remove the sediment

layer that was on top of the fossil layer and excavated a

15-meter square, he said.

They then set up one-by-one grids, “like you would see

in archeological excavations” to sort through and screen

dirt.

“We found about 24 different species, from the mammoth

down to lizards to rodents, antelopes, birds, horses, fish.

We have a really diverse group,” Lewis said. “One

of the students found a great big mammoth tooth.”

One “exciting” find for Kennedy included the mandible

and maxilla of a lizard, “tiny little things,”

Campbell said.

The fossil lizard is Kennedy’s area of interest, or

“focus organism,” as an undergraduate.

“I like them because they are environmentally sensitive,”

she said. “We try to reconstruct the environments that

they came from. When you look at different animals from a

time period, you can see the environmental requirements they

had, if they’re tropical (for example).”

The fossils uncovered by the SHSU team are still in South

Africa. Lewis focuses on the small animals, and when these

fossils are brought to SHSU they will be analyzed in his lab

with the assistance of several students and colleagues.

“It’s a lengthy process (bringing fossils back

to America),” Lewis said. “You dig things up,

and then you have to go back and get a permit to actually

borrow the things you dug up, so it can take a whole year

to get access to the fossils.”

Republic of Botswana

|

Gabidirwe, curator of paleontology

for the Botswana National Museum, Lewis and Thies discuss

their course of action before going inside the Tswana

cave. Part of the SHSU team's goal is to build relationships

with the Batswana so they can take over excavation when

the team leaves. —Submitted Photo.

|

Through his work in South Africa, Lewis became aware of the

Republic of Botswana as an area that could provide him with

information relevant to his research interests.

Botswana is located in southern Africa, nestled between South

Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

This year, he and a team were given the opportunity to work

with the Botswana National Museum to begin the process of

excavating a cave site that preserves fossils between two

million and a half million years old.

“We, as a lab, are real interested in this period because

modern humans are evolving in Southern Africa at this time,”

he said. “We are trying to learn more about what the

environment was like during that period to try to understand

what might have been driving human evolution in the area.”

The team of about 20, including Botswana people, spent approximately

12 days in the area for what Lewis called a “feeling

out process.” At that time, the cave site hadn’t

been thoroughly explored, and very few westerners had ever

even been inside, Lewis said.

“This year in Botswana was really geared toward seeing

if we can work out there, if there was anything there to find

and if we could get the support of the Batswana to help us

to do it,” he said.

It was a much more physical trip than the South Africa dig,

he said.

“We were having to squeeze through crevices full of

bats and spiders, so it’s not a pleasant place to work,”

Lewis said.

“There were spots where the only way to get through

was to get on your back and kind of wriggle down, which is

difficult, especially for someone Tim’s size,”

he said of the 6-foot-4-inch Campbell. “There were cracks

and holes that you had to crawl through that would open up

to bigger pits.”

The Experience

After years of taking students to Africa, Lewis said one

of the things he tries to do is to make sure students understand

what they can expect so they won’t experience “culture

shock.”

“Particularly going on a professional project, it’s

often hard for students,” he said. “I’ve

taken students to Botswana, and they freak out with lions

roaring in the background and people talking in foreign languages.”

The team was in Africa during its winter, and temperatures

ranged from the 80s during the day to as low as the 20s at

night.

“I wasn’t expecting South Africa to be so…it

was a lot like being here,” Kennedy said. “It

looks like Texas, so I didn’t feel like I was really

in Africa when we were in South Africa.”

Botswana was another story. The remote country has only “one

good road,” Kennedy said, with Campbell adding that

it was “20 miles past nowhere.”

In addition, it has the highest HIV rate in the world, as

well as issues with alcoholism.

“None of us, myself included, had been that far out,”

Lewis said. “To be that far away from everything is

really neat. The whole time you feel like you’re on

a journey, this quest, and there’s just this uncertainty

that adds an edge of excitement to the whole thing.”

Adding to the uncertainty, at least at first, was the fact

that they had to travel with the Tswana military, which has

a semi-permanent camp nearby.

“We really didn’t expect it,” Lewis said.

“We didn’t know what they were there for, and

my rule is usually the fewer guns at camp, the better.

“But once we got out there, (we saw that) Botswana has

no fences, and there were leopard prints and lions,”

he said. “Then it’s a little nice to have the

army guys out there to keep an eye out.”

“They were really curious about everything we were doing,

about the States,” Campbell said. “I would chat

them up a lot; their view of the world and their view of American

culture is a lot different than you’d expect.”

One of Botswana’s official languages is English.

The work itself was dirty; “miserable” even, they

said.

“People think it sounds cool, but you don’t really

understand how uncomfortable you are and how you get dirty,

and you just smell awful,” Lewis said. “The caves

are filled with bat guano, so you’re crawling through

bat guano and there are bugs and it’s hot, and then

when you get out, there are no showers.

“We had enough (water) to kind of splash, but we’d

have to take all of our clothes and immediately put them in

bags,” he said. “If we were smart we would have

burned them all.”

“We got back into a bigger town, and we gave our clothes

to these ladies who wash clothes for you,” Kennedy said.

“When we got them back, and they charged us extra because

they were excessively dirty.”

Professional Implications

The team was able to go to Africa through a number of grants

they obtained specifically for the purpose, including funding

from the College of Arts and Sciences.

“The opportunity for an undergraduate to go to Africa

and work on a real professional crew is extremely rare,”

Lewis said.

Campbell, who had taken a year off after graduating from the

University of Rhode Island but had been to Africa twice previously,

was recruited for SHSU’s biology graduate program after

working with Lewis in Africa.

“He worked really hard and he’s obviously really

smart and is really curious about stuff, and those are the

kinds of students you want to go after,” Lewis said.

“I honestly thought his interests were better suited

here than the place he was thinking about going.”

Both Kennedy and Campbell would like to stay in academics

as a career. Kennedy even “generated the contacts needed

to continue with her scientific career, with the next step

being a PhD program at the University of Texas,” said

biology department chair Matthew Rowe.

“It was wonderful,” Kennedy said. “I’m

ready to get back. We’re already working on getting

more grants and raising more money.”

In preparation for next year, Lewis is taking his students

to SHSU’s rock climbing wall for practice. They’re

also planning on collecting books and supplies to send to

villages.

“We want to build relationships with the Batswana and

train some people that are there so they can better understand

the process,” Lewis said. “We can’t work

there forever, and when we leave they can continue to be invested

in the science and the fossils there.”

—END—

SHSU Media Contact: Jennifer

Gauntt

Sept. 5, 2007

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu.

|